March 24, 2020

by eric

Today felt like an inflection point to me. Already so much has happened in the last month; situations that seemed impossible weeks ago are now commonplace, and our thoughts and emotions have evolved accordingly. I want to remember how each day felt, after it’s over.

How did we get here

For me, and for many of us in Seattle, it started feeling real with the tweet on February 29 from a local researcher that concluded that COVID-19 had been circulating undetected and unmonitored for 6 weeks in Washington State.

I had been worrying that since only those recently returned from mainland China were getting tested, we could be missing other cases. The analysis confirmed that fear. I knew immediately that containment had failed. It was clear that there would be no way to do contact tracing for all those people, and there were clearly not enough tests.

My fear for my own family was mitigated to some degree: reports from other countries indicated that most fatalities were for older people, and vanishingly few kids. There was the open question of whether the high estimates of the case fatality rates were inflated by the many who supposedly were asymptomatic or showed only mild symptoms.

My spouse was away on an overnight trip that night. By the time she returned there were already runs on Costco for basic supplies.

Still, while there were quickly tragic clusters of fatalities in local nursing homes, for a few days life continued as normal. We all went to work; the kids went to school, and we started asking what we should do next. Surprisingly rapidly, major tech employers in Seattle (Microsoft, Facebook) sent their workers home. On social media we started chattering about #SlowTheSpread but little concrete action seemed to result.

I started working from home March 6. I was one of the first to do so, and faintly perceived some judgment from a few colleagues–but I thought it was crucial to set the example for my junior teammates that it was okay to do so.

For about a week it felt like we in Seattle were living in the future. Colleagues elsewhere seemed to have little concern. I was on the planning committee for an in-person workshop to be held the week of March 16th on the East Coast. Others on the committee living in other cities saw little reason to change plans, even as European attendees began cancelling their registrations. I pushed for postponement or a virtual meeting, sensing that I would not leave my family in these circumstances. East Coast colleagues argued that they could still meet as a group even if it were not officially the meeting site.

I got in a little bit of a rhythm working at home, picking up some work time normally spent commuting and subtracting some to help deal with kids naps and school pickup and dropoff. My rigged up standing desk on top of my dresser proved functional although the long periods of standing aggravated shoulder problems due to my poor posture.

Colloquium speakers and other visitors to Seattle started cancelling their visits. Airlines sent us frantic emails offering unheard-of deals.

Then on March 11, Seattle Public Schools announced that they would be closing for three weeks–and suddenly working from home got a lot more challenging. On March 12 the governor extended the closure to April 24. With a lively two-year old and an intense five-year old to keep entertained it looked insurmountable. (Just the two weeks at home around Christmas we thought was hard!) We repartitioned our day so I could squeeze in work intervals and calls in between helping with the kids. My spouse took the lead organizing “Family School,” and our oldest did some worksheets in the morning, a family walk mid-morning, Snap Circuits during brother’s nap, another walk mid-afternoon, and then we all faded into screen time in the late afternoon. I felt jealous of my child-free colleagues working under what I imagined might be easier circumstances, perhaps even enjoying a pleasant boost of productivity thanks to all the cancelled meetings.

We held virtual visiting days with our admitted graduate students, pitching them on UW and Seattle when everyone was trying to stay far away from us. All my colleagues were working from home.

On March 14 our oldest spiked a fever, and then there were no more walks. For two and a half days he had a minor fever–and then my spouse got it as well. Our youngest was in the midst of a snotty cold. My spouse spent four hours on hold to talk to a doctor virtually, who didn’t recommend a test as it wasn’t a classic presentation of COVID-19. Maybe it was just the flu? Though we had all had flu shots.

Since we couldn’t go to the stores we turned to online delivery; some poor shopper spent an hour texting us pictures of empty shelves and asking us what we wanted to replace out-of-stock items with. We quickly learned to start the next order right away to “hold our place” as available delivery dates stretched out to almost a week later. Items started to vanish from stock on Amazon.

I spent a lot of time on Twitter, frustrated that there was no progress on getting tests moving on a massive, industrial scale, wondering why a war-like mobilization to manufacture the ventilators we would so clearly need very soon wasn’t starting. Why were we wasting this time instead of preparing? I watched the President deny the crisis, undermine the scientists around him, and fixate on the stock market rather than dealing with the actual pandemic. Every company with my email address sent me a message telling me about the precautions they were taking.

Famous people tested positive. All the sports were cancelled.

We held our workshop fully virtually, with me sneaking in sessions on my phone while watching kids or during naps. Our oldest recovered from his fever only to relapse scarily a few days later. I found myself with a low fever and mild shortness of breath. Were they psychosomatic? Was my thermometer reliable? I knew there was no point calling anyone about them. All of the pulse oximeters on Amazon were sold out.

We started to hear scary stories from Italy. Harvard sent all of its students packing for home with one week’s notice. Colleagues elsewhere were working from home and figuring out the virtual backgrounds feature of Zoom. Those of us with kids made lots of silly jokes on Twitter.

California issued a shelter in place order, but we still didn’t have one in Seattle–and there still seemed to be some people going about their lives as normal. The stock market did giant belly-flops over and over, and I wondered why I hadn’t thought to move our small retirement funds into cash at the beginning of the month.

Bars and restaurants were closed. Those of us fortunate to have salaried jobs heard of mass layoffs in more precarious industries. Seattle’s mayor issued a moratorium on evictions. Young, healthy people started giving first-person accounts from the ICU.

My department chair spearheaded a local drive for unused N95 masks, seeding similar efforts nationwide. My spouse wrote a reflection on Instagram that was seen by millions.

We spent a lot of time in our small, thankfully fenced front yard, enjoying some warm spring weather and dreaming up little games to try to distract the kids a little while longer until iPad time. Finally everyone was healthy again.

Yesterday & Today

Last night our governor issued a “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order shutting down remaining non-essential businesses, spawning a surge of bureaucratic emails today.

A few of the remaining holdout telescopes have now halted operations.

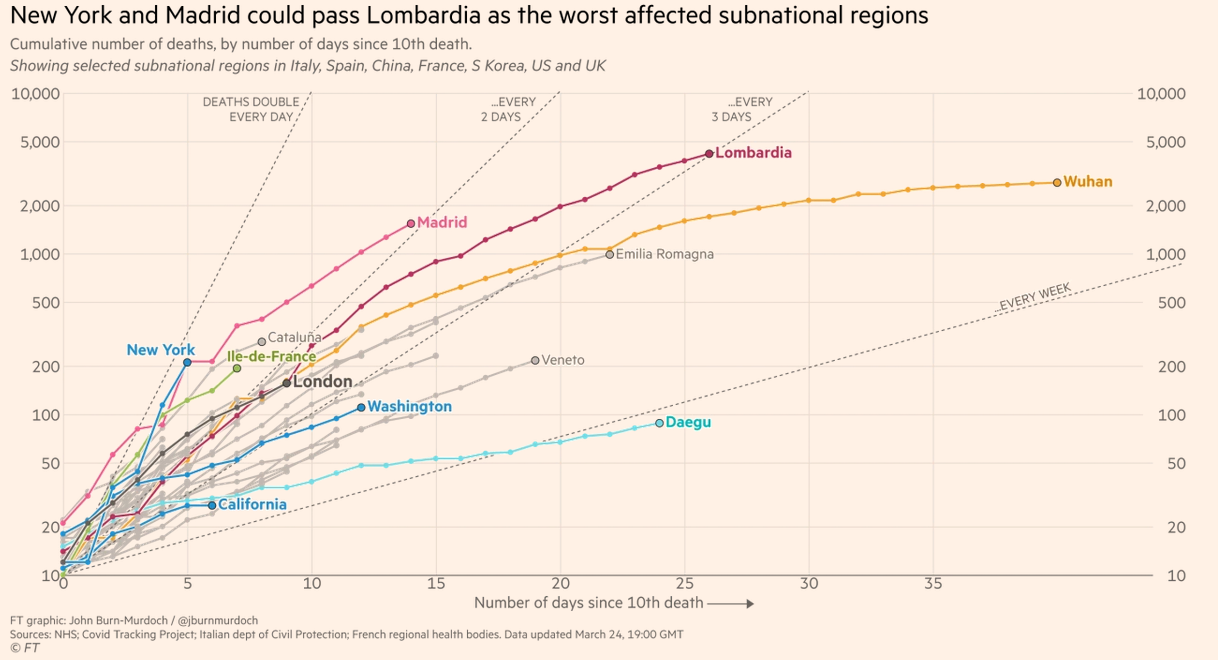

Various quantitative people who are not epidemiologists are arguing about whether this is all blown out of proportion, whether to plot per-capita or totals, whether the number of confirmed cases is meaningful, etc. Deaths are unambiguous but a trailing indicator given the long incubation time and the time to get truly sick.

After waffling for awhile, Boris Johnson delivers a forceful message locking down the UK.

A chart indicates Seattle has a slower growth in death rates than other places–have our social distancing measures helped? How long can we sustain them? Have we done anything to stop a resurgence once they are lifted?

Cases in New York City have rocketed past Seattle, and there are some grim signs (lines outside to enter an ER?). This feels like a turning point.

The President suggested we just restart everything by Easter.